A Mini-History of Dance & Flyers

I

Warm Up

II

A Mini History of Dance Education

DECEMBER 1, 2009, PUBLISHED BY IN DANCE

A

Dance

has been a part of U.S. public education since the early 1900s, when

the concepts of gymnasium and open-air exercise were becoming popular in

Europe. National dances were developed, taught, and situated in the

gymnasium, which emphasized the importance of attending to both the

child’s physical and intellectual development in schools. Around the

time that John Dewey (1), most noted for his education reforms, was advocating curriculum to enhance democracy, Gertrude Colby (2)

developed the “natural dances,” mirroring the return to the Greek ideal

found in contemporary art circles. Popular dancers such as Isadora

Duncan (3) and her protégés emphasized movement founded on the law of natural motion and rhythm.

“The

leaders of this movement went to the Greeks because they had accorded

dance so high a place in the education of youth. From the Greeks, the

leaders learned again the educational value of dance and the need for a

technique which rests upon fundamental, natural principles, and not upon

unnatural body positions.”

B

Many books for teachers were written during this time, such as Caroline Crawford’s (4) Dramatic Games and Dances for Little Children and Agnes and Lucile Marsh’s (5) The Dance in Education.

Such books began with a preface on the importance of educating the

whole child and attending to children’s creative process. Crawford, for

example, suggests that children begin relating, organizing, and

composing their experiences into wholes before mastering complex

symbols. Although she writes with almost prophetic understanding of

children’s artistic development, her book, like the others of the time,

follows the theoretical introduction with a hundred pages of a musical

score and movement games written by adults instructing exactly how the

game or dance should be executed.

C

By the late 1920s science, too, began influencing the dance curriculum. Margaret H’Doubler (6)

began the first teacher training program in dance, centered on an

understanding of the science and rhythmic underpinnings of movement,

which developed into the Wisconsin Idea for Dance. A basketball coach,

H’Doubler attended graduate school for philosophy New York in 1916. Her

supervisor, Blanche Trilling, then chair of the Wisconsin Physical

Education Department, urged her to discover an appropriate dance “worth a

college woman’s time.” H’Doubler, who had studied with Dewey, believed

the future of dance as a democratic art activity rested with our

country’s educational system; she returned to Wisconsin with a theory

for teaching dance conceptually, “a theoretical framework for thinking

about and experiencing dance and a philosophical attitude toward

teaching it as a science and a creative art.”

D

In a call for holism, Emile Jacques-Dalcroze (7)

developed his work in Eurhythmics in the 1920s and ’30s. Adapting

musical study to rhythmic movement exercises or “moving plastic,”

Dalcroze argues, in his book Eurhythmics, Art and Education, for

the use of rhythmic exercises to “break natural patterns” and “strive

for mental and physical equilibrium.” Concentration, relationship to

work, reflex action, and “free play and expansion of imagination and

joy” were the goals of his approach to children’s movement and music.

E

In the 1930s Rudolph Laban (8) combined scientific inquiry with the natural as he wrote extensively about dance education, particularly modern dance. In Modern Educational Dance Laban

makes a case for modern dance over ballet, presents a complete

developmental plan for children dancing from birth through adulthood,

and introduces his seminal work on movement analysis. He offers his 16

Basic Movement Themes concerned with the body in space, with weight;

describes his early effort experiments and the eight basic effort

actions, which have to do with force; and begins describing ways to

think about and observe movement by dividing space into a sphere—the

seed of Labanotation. We creative dance educators owe our understanding

of movement concepts to Laban’s work through his protégé Irmgard

Bartenieff.

F

In

the 1950s, the growing popularity of psychology and its influence on

the educational curriculum heavily impacted dance education. Like their

early childhood contemporaries, dance educators added the development of

self-esteem as a rationale for their work. Individual awareness and

expression were the themes of the decade’s creative dance books, such as

Gladys Andrews’ (9) Creative Rhythmic Movement for Children.

Andrews speaks to the importance of creative dance for the “whole”

child and describes a teaching process resonant with today’s learning

theories, such as constructivism, theories of multiple intelligences,

and critical pedagogy. For example, she describes how teacher and child

learn together through movement experiences. With an advanced degree in

education, Andrews writes of a child-centered curriculum as different

from learning that presumes the child is a “receptacle.” She states,

“[C]ompetent teachers must know and understand children. They must know

why they act the way they do and why individual differences among

children are so important in the educative process.” Andrews not only

describes the child as whole—body, mind, emotions, interrelated and

interactive—but also (like the Reggio Emilia teachers of 1999) includes a

Children’s Bill of Rights in Creative Rhythmic Movement.

G

The

1960s and ’70s were foreshadowed by Andrews’ “open classroom” movement

and the concurrent advent of brain research, informing educators about

the right and left hemispheres of the brain and their independent and

intertwined functions for cognitive development. These two movements

were another manifestation of the combined natural and scientific

rationale used for dance education throughout the century. Dance

educators such Geraldine Dimondstein and Mary Joyce (10) were two

major influences during this time. Dimondstein was verbose,

intellectual, and philosophical, Joyce practical and accessible; both

concerned themselves with defining the elements of dance in language

they believed would speak to the classroom teacher. Their practical,

informative books are still considered essential by most dance educators

today.

H

By 1980, youth had been watching television for three decades and faced problems of increased societal violence as well as the availability of drugs and guns. Children were often left at home to watch TV as parents spent more time at work. In 1980 Barbara Mettler (1907 - 2002) published her Manifesto for Modern Dance (1953) in which she explains that "Dance is a motor art, directed toward satisfying the kinaesthetic sense." (25) In 1980, she published The Nature of Dance as Creative Art Activity through which she explains:

“Dance is an activity which can take many forms and fill many different needs. It can be recreation, entertainment, education, therapy and religion. In its purest and most basic form, dance is art, the art of body movement”.

With the ’80s and ’90s came aerobics and

the fitness craze, which replaced dance and other artistic movement

preferences.

Some

dance curriculum books started replacing the word dance with movement.

These books emphasized the physical, scientific, motor, and kinesthetic,

and provided step-by-step instructions for the teacher to implement

activities without having to understand the conceptual and underlying

principles of dance. Sheila Kogan’s (11) Step by Step: A Complete Movement Education Curriculum from Preschool to 6th Grade offers

a prescription for teaching the movement exercises she developed,

including a script of the first class. The introduction lists three

benefits of a movement program for children: training for children with

motor problems, tools for teaching academic skills, and training for

“normal” children. According to Kogan, “Most children are out of shape.

They are not necessarily fat but they do not have the agility, strength,

or endurance that they could and should have. Most children have weak

stomach muscles, bad posture, and a tendency to stop any activity when

they feel the least bit tired.”

I

In

the 1980s and 1990s, economics and politics had a major impact on both

education and the arts. As conservatives clamored for a back-to-basics

approach to education, the arts became even more marginalized as

extracurricular, not worth funding in that belt-tightening decade. Dance

was considered a frill. The disappearance of art programs furthered the

notion that the arts were superfluous to the more important work to be

accomplished in school. In fact, both arts and education programs lost

funding. As schools became more crowded, classes took over multipurpose

rooms and gymnasiums. Some schools dispensed physical education and

dance teachers.

J

Ironically,

the fields of neuroscience and educational research were reintroducing

the works of Dewey, Piaget, Paolo Freire, and Vygotsky (12) and

reestablishing the social justice themes embedded in the multicultural

and feminist pedagogical frameworks of the ’60s and ’70s. Teacher

education programs focused on child-centered learning such as Bruner’s

spiral curriculum (13), whole-language literacy (14), Howard Gardner’s (15) theory of multiple intelligences, constructivism (16), and liberation pedagogy (17).

The arts, offering multiple symbolic approaches to learning, were

resurging just as the schools were expunging the arts. Dance educator

Sheila Vasquez (18) expressed the paradox: “This conservatism

supports older paradigms of teaching which make distinctions between

talent and intelligence, which compartmentalize learning and create

polarity between body and mind, and which emphasize an elite structure.”

Arts education was then undergoing its own research endeavors. The largest was the Getty study (19),

“Beyond Creating: The Place for Art in America’s Schools,” which

generated a field-wide dialogue about the role of arts in education,

with the most prolific debates about Discipline-Based Arts Education

(DBAE) (20), a topic beyond the scope of this article.

K

Popular dance educators Anne Green-Gilbert and Susan Stinson (21) expanded the early frameworks of Laban and Bartenieff (22)

into dance curriculum grounded in contemporary learning theories, brain

research, and critical pedagogy. Gilbert founded the Creative Dance

Center in Seattle, Washington, and has become an international figure in

brain/body dance for children. Stinson, working out of the University

of North Carolina, continues to push the field forward with provocative,

research-based discourse on the purpose and practice of dance

education. Both worked with professionals within the National Dance

Association (23) and National Dance Education Organization (24) to develop national standards for dance.

This article appeared in the December 2009 issue of In Dance.

Patricia Reedy is the Executive Director of Creativity & Pedagogy at Luna Dance Institute. A lifelong learner, she enjoys sharing her inquiry process with others.

1

John Dewey: America's philosopher of democracy and his importance to education

In Dewey’s model, art isn’t a thing, it’s an experience (though a thing might be the catalyst for the experience.) The work of art isn’t so much the painting or string quartet as it is the experience of the painting or string quartet. That experience depends completely on the social context both of the work’s creation and of its audience. We shouldn’t ask, “what is art?” but rather “when is art?”

Dewey saw art not as something existing separately from everyday life, but as existing on a continuum with mundane pleasures. The Stanford Encyclopedia:

Dewey then argues that we must begin with the aesthetic “in the raw” in order to understand the aesthetic “refined.” To do this we must turn to the events and scenes that interest the man-in-the-street such as the sounds and sights of rushing fire-engines, the grace of a baseball player, and the satisfactions of a housewife. We find then that the aesthetic begins in happy absorption in activity, for example in our fascination with a fire in a hearth as we poke it. Similarly, Dewey holds that an intelligent mechanic who does his work with care is “artistically engaged.” If his product is not aesthetically appealing this probably has more to do with market conditions that encourage low-quality work than with his abilities.

2

3

4

Dramatic Games & Dances For Little Children.

The Dance In Education, Second Edition, By Agnes L. Marsh And Lucile Marsh

6

7

8

Laban/Bartenieff Institute of Movement Studies, LIMS (New York City)

9

Creative Rhythmic Movement for Children by Gladys Andrews

By Geraldine Dimondstein and Mary Joyce

LINK

A Mini History of Dance Education

-----------------------------

Questions

After

reading the article A Mini History of Dance Education and the materials

presented in this post, answer the following questions:

1. According to John Dewey, what was the importance of art in education?

2. What was Gertrude Colby's goal when she developed the natural dances?

3. What was the drawback of Caroline Crawford's dramatic games & dances for little children?

4. What did Margaret H’Doubler believe about dance education?

--------------------------------------------

--------------------------------------------------------------------

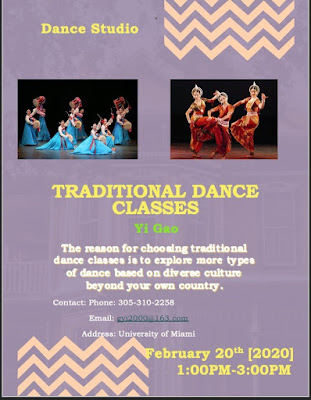

FLYER

Assignment

Create a flyer to advertise your dance class. Include the following:

Title of the Class

Name of the school/studio/program

Your name

Credentials

Age group you are teaching

Day and Time it takes place

Contact: Address/ Telephone / Email

Benefits: Why should anybody take your class

------------------------------

How to Effectively Design and Distribute Event Flyers

7 Effective Ways to Promote Your Classes

-----------------------------------

Samples of Students' Work

Comments

Post a Comment